One question I get from customers is whether it is possible to weld stainless steel and mild steel together…

To answer shortly, yes, you can weld stainless steel to mild steel using a compatible filler material like a 309L stainless steel filler rod. Proper surface preparation and heat control are key factors for a successful weld.

These metals share enough properties that welding them together is possible.

However, you must weigh up if it is worth it for your project, as there are many factors and potential problems that you need to understand before welding these metals together.

Key Differences Between Stainless Steel & Mild Steel

Stainless steel and mild steel may be similar metals, but they have differences that you need to know. Don’t get tempted to skip over this information.

Understanding what separates these materials is the first step to welding them together.

Composition

Both types of steel are iron-based. Stainless steel can have up to 80% or as low as 50% iron, but mild steel is usually around 99%.

Steel is stainless steel if it has at least 10.5% chromium which gives it corrosion resistance.

Mild steel has little to no chromium but has up to 0.25% carbon, while stainless steel has less than 1.2% carbon content.

The addition of other alloying elements is what gives the steel its specific properties.

Corrosion Resistance

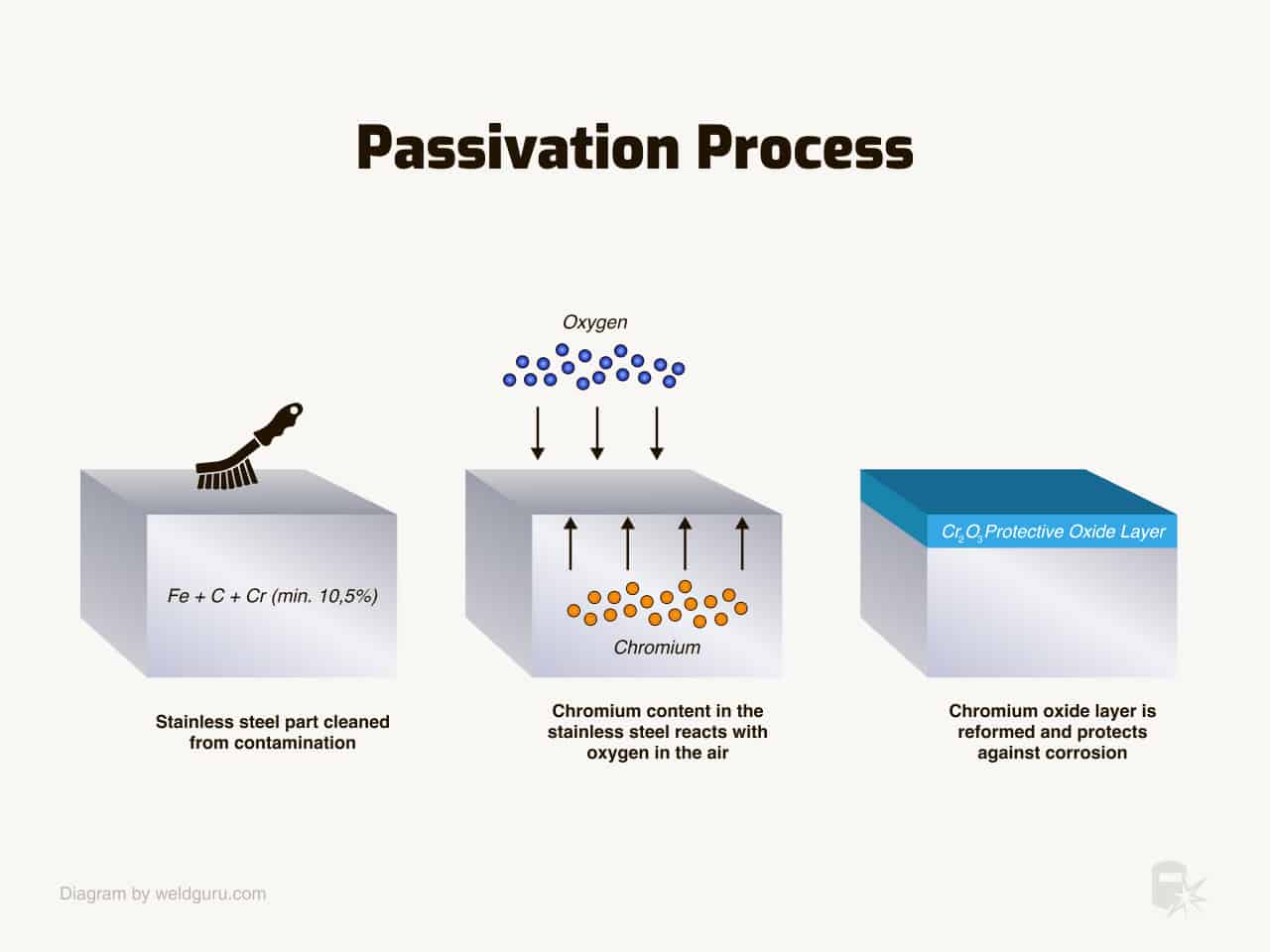

The large amount of chromium in stainless steel is the force protecting it from rusting. Chromium reacts with the oxygen in the air to form chromium oxide in a process known as passivation.

© weldguru.com – Image usage rights

This layer of chromium oxide is invisible and repairs itself when the surface gets scratched or damaged. Some grades, such as 316, have more chromium, increasing the corrosion resistance.

Mild steel has no alloying elements that prevent the oxygen in the air from interacting with its iron.

So, when the iron comes into contact with oxygen, it creates iron oxide, also known as rust. Over time, mild steel will oxidize until the iron is gone.

Strength and Hardness

Since both types of steel have many different grades and alloys, you should compare the strength of specific grades rather than as a whole.

Generally, stainless steel is stronger, depending on the grade. For example, 304 stainless has a tensile strength of between 500 and 600 MPa, while mild steel is between 300 and 400 MPa.

One aspect often overlooked is that stainless steel is high strength and has a higher density than mild steel. So, stainless steel has a higher strength-to-weight ratio than mild steel.

Stainless steel has chromium and nickel, increasing its hardness over mild steel. Yet, this has the effect of also reducing its malleability when compared to mild steel.

The result is that stainless is harder and more resistant to impact, making it challenging to form.

Mild steel is easier to bend and shape because it is much softer, leaving it prone to damage from impacts and wear.

| Stainless Steel | Mild Steel |

|---|---|

| Higher chromium content | Low chromium content |

| Highly resistant to corrosion & rust | Higher risk of corrosion & rust |

| Visually appealing | Not very visually appealing |

| Higher cost | Lower cost |

| Lower thermal conductivity | Higher thermal conductivity |

| Superior surface with lustrous finish | Dull matte finish |

| Includes various alloying elements | Alloying elements available in very low quantity |

| Wider applications due to good weldability | Good usage with great weldability |

| Available in various types of grades | Available in higher carbon content lowering its weldability |

The Metallurgical Compatibility of Stainless Steel & Mild Steel

Although stainless steel and mild steel seem like different metals, most welding processes can join them. So, before diving into how to weld these metals together, let’s discuss what’s inside them and how that relates to their weldability.

As I mentioned in the previous section, mild steel and stainless steel have a high percentage of iron. The difference will be the amount of that iron and the other added elements.

Since stainless steel has a higher percentage of alloying elements, its iron content will be much lower. For example, 304 stainless steel has about 18% chromium and 8% nickel, leaving no more than 74% iron content.

The added elements in mild steel make up a tiny percentage of the composition, often less than 1%. This means mild steel will have an iron content of around 99%.

As you heat stainless steel to high temperatures, chromium likes to bind with any carbon it finds floating around.

The result is the creation of chromium carbides and less free chromium to form the protective chromium oxide layer.

This can cause a problem when these carbides cause corrosion in the grain boundaries of the weld.

Chromium consumption can also cause corrosion around the heat-affected zone of a stainless steel weld. Even when welding stainless to stainless.

Adding nickel to stainless steel helps toughen the weld metal, reduce solidification cracking, and improve corrosion resistance.

Since nickel is vital to maintaining a good weld, it’s important that the weld metal has enough nickel.

The Challenges in Welding Stainless Steel to Mild Steel

Now that you know that you can weld stainless steel and mild steel together, you need to know what challenges await you.

Potential Corrosion Issues

Mild steel is prone to rusting, while stainless steel won’t rust as readily. So, once you’ve decided to weld them together, you must consider what role corrosion will play in the finished product.

Since the mild steel side of the weld joint is prone to rust and other corrosion issues, you’ll need to protect it from oxidation. The most inexpensive and straightforward way to do this is to apply a coat or two of good-quality paint to the mild steel.

You shouldn’t stop there, though.

The stainless steel side can also rust after using too much heat during welding. When you weld stainless steel too hot, the chromium will bind with carbon. When this happens, there is insufficient free chromium to form the protective oxide layer.

A good practice is to paint the weld joint up to the edge of the heat-affected zone on the stainless steel side of the joint. Doing this will help to prevent any corrosion issues that may arise.

Anytime I’ve had to weld stainless steel to mild steel, I’d paint the mild steel side, the weld bead, and the heat-affected zone on the stainless steel.

Difficulties in Heat Control

Mild steel and stainless steel react to heat differently, so managing heat is essential. Aside from this, when you hold these welds at high temperatures for too long, warping, cracking, corrosion, or brittleness can occur.

When you expose austenitic stainless steel to high heat, carbide precipitation will form, which decreases its corrosion resistance. Also, high heat increases the odds of cracking, pitting, or other weld faults.

The best way to control these issues is to limit the heat and time you expose the metal to that heat. I like to weld at the lowest amperage possible, which gives me a sound weld with good fusion.

When I have to weld stainless steel to mild steel, I like to run some beads on scrap metal of the same thickness, type, and joint configuration. Then, after welding, I inspect the weld for flaws or other problems, sometimes cutting the weld joint in half to check for proper fusion.

For the actual welding, there are a few strategies to help control the heat input:

- Backstep or stitch welds

- Pre-heat treatments

- Insulating the weld after welding to slow cooling

The most important piece of advice I can give you is to practice the welds on scrap pieces before even fitting up the joint. Never use the piece you are working on to experiment with settings.

Problems with Material Distortion

Thermal expansion and conductivity differ enough between these two steels to cause problems as you weld them together. Before starting an arc, you’ll need to consider this and plan how these factors affect the finished product.

Stainless steel has less thermal conductivity and higher thermal expansion than mild steel. This means stainless steel distorts much easier when heated and holds its heat much longer than mild steel.

When the two sides of a weld joint expand and heat differently, the expansion and contraction could be severe enough to cause the weld joint to break apart. Even if the weld joint stays intact, the weld may crack under stress.

Distortion of the stainless side of the weld joint will be the more likely problem you’ll encounter.

There are a few ways to fight distortion:

- Control the heat input.

- Use techniques such as backstepping or stitch welds

- Do not use tight weld joints in your fabrication. Leave some room for thermal expansion.

- Use chill bars, strongbacks, or bracing on the stainless side of the joint to cut distortion.

- Use pre and/or post-heat treatments.

The best weapon to fight distortion when welding mild steel and stainless steel is predicting what could happen.

Once you know what might happen, you can plan how to stop it from happening.

The Different Methods of Welding Stainless to Mild Steel

Now that you know the issues you will face during welding, it’s time to talk about the welding itself. Before covering the individual processes, you must know what to use for filler metal.

Most of you reading this will be welding austenitic stainless steel to mild steel.

In this case, you’ll want to use 309L for your filler.

This is the best all-around filler metal used to join these metals. Fortunately, it is also available for most of the common welding processes.

MIG Welding (GMAW) Stainless to Mild Steel

MIG welding (GMAW) is the most straightforward welding process for beginners. When welding stainless steel to mild steel, it will be the most user-friendly and easiest to master.

You’ll want to use ER309L wire, a high argon shielding gas, or a trimix gas for MIG welding stainless to mild steel.

The choice of shielding gas will come down to what you want to do with this weld and the type of transfer you will be using.

For example, some tri-mix gases are best for short-circuit transfer, and gasses with helium will transfer more heat to the weld and base metal.

I often use a 98% argon/2% carbon dioxide gas for MIG welding stainless steel to stainless steel and mild steel.

When using MIG to weld mild steel to stainless, I like to use the same technique when welding either stainless to stainless or mild steel to mild steel. You’ll only want to be careful of the heat you use.

Pros

- Easy to use

- Can handle thin and thick sections

Cons

- Typically requires a tri-mix shielding gas which can be costly

Additional read: MIG Welding Stainless Steel

TIG Welding (GTAW) Stainless to Mild Steel

TIG welding (GTAW) is difficult for beginner welders to learn and requires costly equipment.

The challenge of TIG welding is you must control the amperage, filler metal, arc length, travel speed, and torch angle simultaneously. It takes a steady hand, patience, and practice to master.

© weldguru.com – Image usage rights

But TIG welding is the best option for thin sheet metal because it allows for the greatest heat control. Most TIG welding machines do not have the required amperage to weld thick materials, which puts them at a disadvantage versus the other three options.

The amount of control you have over the welding process is a significant advantage because you can adjust many factors on the fly. The problem comes with the advanced skill that TIG requires of the welder.

You will use a 309L filler rod and a 100% argon shielding gas.

Pros

- Good for thin materials

- Allows for the greatest control

- Produces the best-looking welds

Cons

- Difficult to master

- Slowest process

- Equipment is expensive

Additional read: TIG Welding Stainless Steel

Flux-Cored Arc Welding (FCAW) Stainless to Mild Steel

Whenever I have to weld stainless steel in thicknesses of 1/4” or more, I always turn to flux core. This process is fantastic for welding stainless steel, as well as welding stainless to mild steel. Flux core is especially great for welding thick sections together.

I would recommend using a shielding gas with flux-core (dual shield flux core welding), as it provides a better level of protection against contamination for the stainless steel.

You’ll want to use 309L wire and either 100% carbon dioxide or 75% argon/25% carbon dioxide mix for shielding gas. I like using the 75%/25% gas because the welds look nicer, and the weld metal flows better, giving me a weld with good fusion.

Flux-core is not suitable for welding thinner materials because the wire diameters and amperages are too high for sheet metal. Making burn through a very likely occurrence.

Like MIG welding, I use the same technique for welding mild steel to stainless steel as I would if it were stainless steel to stainless steel.

One downside I have found when using flux-core is that it produces a lot of smoke which can be toxic. Therefore always weld a well-ventilated area and/or wear a respirator.

Pros

- Good for thick materials

- Easy to use

- Gives a nice-looking weld

Cons

- Not good for thin metals

- Produces lots of smoke

Stick Welding (SMAW) Stainless to Mild Steel

It is possible to weld stainless steel to mild steel using stick welding.

Stick welding does not use any shielding gas, instead relying on the burning off of the flux coating around the electrode to provide the shielding from atmospheric gases.

This flux likes to absorb moisture in the air, which can lead to the electrode sticking, an unstable arc, and porosity.

The one advantage that stick welding holds over all the other processes mentioned here is that it does not need expensive equipment and is excellent for welding in the field.

Like the other processes, you’ll be using a 309L welding electrode.

Like flux-core, stick welding stainless and mild steel is best used on thicker materials (more than ¼”).

Pros

- Equipment is inexpensive

- Best for use in the field

- Does not need shielding gas

Cons

- Electrodes can absorb moisture

- Not suitable for thin materials

- Electrode likes to stick to the base metal when striking an arc

- Don’t have the best control over the weld

| MIG | TIG | Flux Core | Stick | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difficulty | Easy | Most difficult | Easy | Hard |

| Filler Wire/Metal | 309L | 309L | 309L | 309L |

| Control | Good | Excellent | Good | Poor |

| Quality | Good | Excellent | Good | Poor |

| Speed | Fast | Slowest | Fast | Average |

| Suitable for Thin Metals | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ |

| Suitable for Thick Metals | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ |

Wrapping It Up

Welding stainless steel with either stick, MIG, flux-core, or TIG is possible and well within the skill level of the beginner welder.

However, you should consider if it is necessary as the risk of corrosion and the additional cost of gas may not be worth it for your needs.

As long as you take the time to consider all the factors involved and take care to account for all the issues you may encounter, there is little reason that you wouldn’t be successful.